Interview by Unam Ntsababa

*Responses edited for length and clarity.

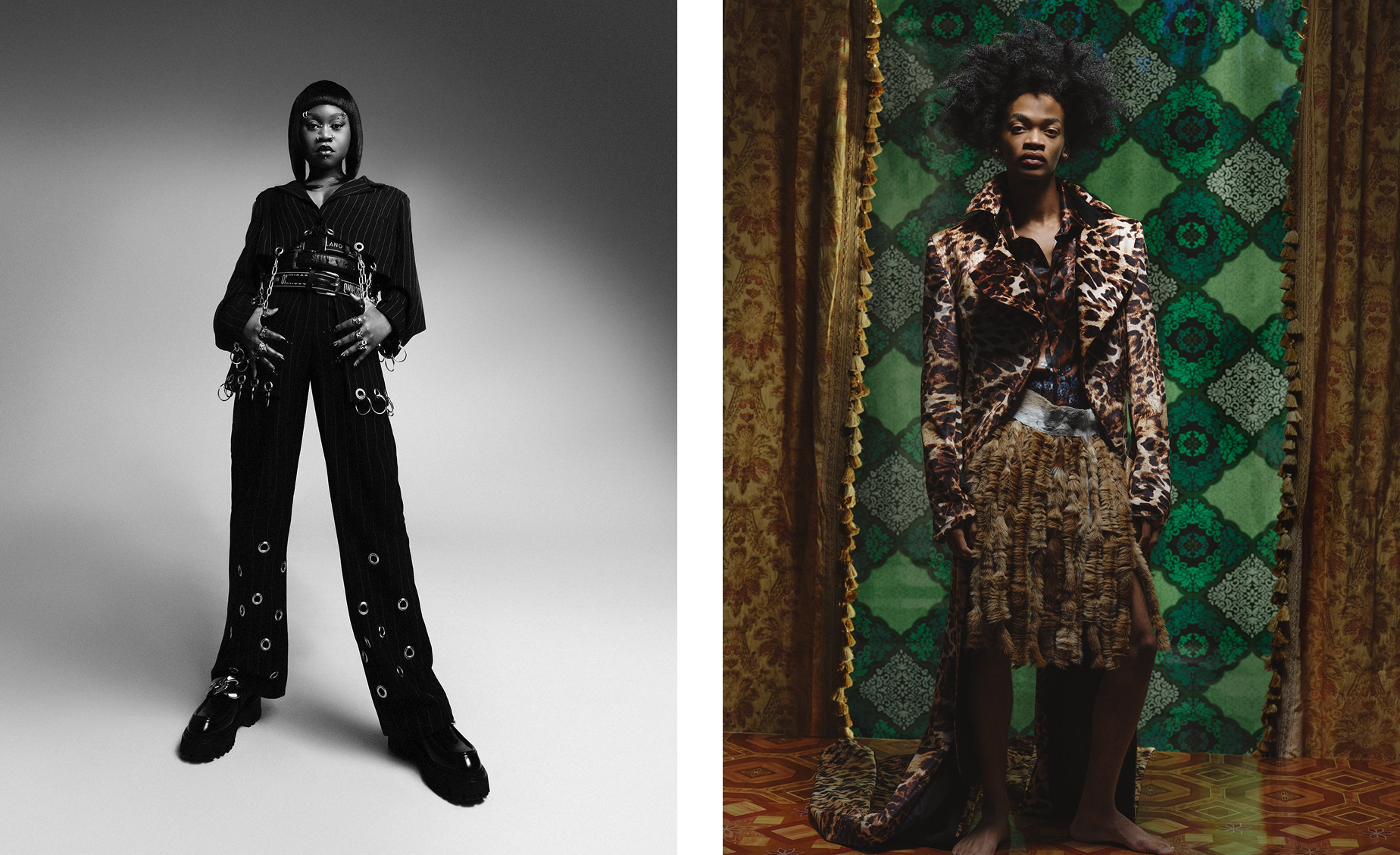

In the expressive universe of Siyababa Atelier, fashion is never just fabric; it is ritual, rebellion, memory, and a deeply personal method of healing. Founded by designer and creative force Siyabonga Mtshali, the Johannesburg-based label has gained attention for its sculptural silhouettes, Gqom-inspired couture, and deeply introspective collections. But behind the garments lies a story rooted in KwaZulu-Natal, grief, queerness, and a designer’s refusal to be boxed in by the fashion industry’s conservative expectations. In this conversation with Mtshali, we speak about the politics of beauty, the Skhothane movement, grief as creative fuel, and whether South Africa is ready for the kind of liberation Siyababa represents.

Growing up Zulu and queer – what did beauty mean to you before you had the words or tools to define it?

To be very honest, the person that Siyababa is right now is the person a younger version of myself wanted to be. I grew up in a Christian home – my mother was a teacher, and you can imagine how strict teachers are. Everything had structure and discipline. That’s what she enforced with her students and naturally with her son too.

So when I looked outside, especially during the Skhothane culture era – the Carvella’s, the segments that Third Degree had of what was going on in the townships, I felt excluded. Even though I grew up in the hood, I couldn’t be part of that beautiful culture because of these restrictions. I didn’t get a Carvella and iBrentwood because my mom thought that was associated with specific cultures. Those were the things I found beautiful. And now, in Johannesburg, where I have all the freedom, I embrace that beauty and that culture.

Beauty, to me, is finally being yourself.

Do you remember the first time fashion moved you, not as something to wear, but as something to say?

The Skhothane culture definitely inspired me. I’ve always been attracted to things that are expressive and loud. I believe art is supposed to create conversation. At the time, your Khanyi Mbau’s were being scrutinised because they came from a place of luxury, and I’d watch Third Degree with my parents because they wanted us to be aware of the world. But the Skhothane culture had the opposite effect on me – it made me more attracted to it because they looked like individuals. That culture is still a strong trait in my work today.

Your work blends mourning, memory and movement. Is fashion your archive, your ritual, or your rebellion?

It’s an archive, but I think it’s something a little bit stronger than that, because there are good and bad memories, there’s loss. Growing up in KwaZulu-Natal and being the only boy ekhaya, you become a pillar of strength and start minimising your emotions. Fashion is a method of therapy. I’ve been trained to suppress emotions like sadness and grief, and art helps me process them. So it’s therapy for a young Zulu boy.

Tell me about the role of grief and healing in collections like Siyazila. How do you stitch emotion into fabric?

It’s not my first time basing a collection on a family member’s death. My first collection, Sibabi, was during my graduate year in 2019. It was about facing my fears after losing my dad: my biggest supporter, the person who funded fashion school. After his death, I started experiencing nightmares. I turned the figures from those dreams into silhouettes. I made the nightmares into garments.

With Siyazila, I didn’t want to look at my sister’s death as something dark or sombre. I wanted to celebrate her life. She was bold, expressive, and introduced me to Gqom. Siyazila is a memory of who she was, not her death.

How does spirituality inform your designs? Do you feel guided by forces beyond you?

I grew up Roman Catholic, but it wasn’t something I felt deeply connected to. Death introduced me to spirituality. I felt closer to my father and sister after they passed. I don’t believe they’re far from me. Every idea and opportunity that comes up, I believe it’s my ancestors steering me. So everything I do isn’t just touched by me as Siyababa, but by my entire lineage.

What’s a garment or collection you made that you think wasn’t fully understood, but needed to exist?

There’s a leather dress from Siyazila with crocodile skin and gold eyelets. It has this alien aesthetic. The back is tied with a rope that people could associate with suicide, but it’s not about that. It’s about the suffocation and anxiety that comes with grief. You carry that weight on your back. I was scared it would be misinterpreted until I spoke to uDesire Marea. They said, “You’re not doing it for the people. This is your method of healing.” That freed me.

Do you feel seen by the South African fashion industry, or do you exist on its edges?

I nearly gave up fashion in 2023. I was too artsy for the fashion space, but too fashiony for the art space. I was in limbo. No, I don’t think I’m seen. Not yet. People don’t know where to place me, but hopefully, the rest of the world will. South Africa is a very conservative country, and we need to accept that we’re still very early in our conceptual fashion space. I don’t expect everyone to digest everything Siyababa Atelier does.

You said something powerful about South Africa being conservative. What do you think African fashion needs to let go of to become truly liberated?

Africa needs to let go of European standards of beauty. Our continent has rich culture, colours, silhouettes, beads. We have 11 official languages in South Africa alone, each with a unique aesthetic. But too many designers look to your Diors and your Schiaparelli’s. We start mimicking instead of creating. We become a continent of counterfeits instead of creativity.

We need to research and investigate our own ideas of beauty.

If you could design something in complete freedom — no budget, no gatekeepers — what would that look like?

I don’t know what it would look like, but I know what it would feel like. I want to create something that sparks conversation, where one group loves it and another hates it. I’d use natural hides like stingray leather and zebra print. I’d create a hybrid animal — different textures, skins, horns — something femme fatale, something people want to touch but also feel disgusted by. It would belong in a museum, not a runway.

Siyababa Atelier is not here to be liked — it is here to be felt.